Below is the full text of our submission, as presented to the National Treasury.

Submission regarding Fiscal Anchor Discussion Document

[Download the Fiscal Anchor Discussion Document]

Analysts: Peter Attard Montalto with Tian Cater

Krutham welcomes the opportunity to provide input on the Fiscal Anchor Discussion Document and the subsequent market consultations led by National Treasury. Our submission does not revisit the extensive theoretical foundations of fiscal anchors but instead sets out the key design features and institutional requirements that we believe are essential to cement fiscal credibility in South Africa and lead to a lower, flatter yield curve. Overall, we found the discussion document useful but it lacked a definitive narrowing of the options to a comprehensive enough conclusion, which is what we try and achieve here.

Summary

In summary, we propose the adoption of an integrated fiscal anchor with the following multi-layered structure:

- Overarching objective: a debt-stabilising primary balance, formalised as the anchor.

- Operational rule: a compositional expenditure/GDP ceiling, combined with binding minima for growth-enhancing spending share of total spending (infrastructure, capital maintenance and selected social outlays).

- Eventual transition: a binding level debt anchor once stabilisation is achieved, consistent with international best practice.

Additionally, to embed credibility, we recommend stronger parliamentary oversight – requiring each administration to table a macroeconomic policy plan aligned with the anchor – and a clear, transparent and extensive macro-fiscal strategy published alongside the Budget and MTBPS.

The biggest hurdle in our view is institutionalisation. A credible anchor depends on strong, independent oversight. Capacitated fiscal councils to scrutinise assumptions and monitor compliance are essential. Better capacity for actual independent fiscal forecasting from the Fiscal and Finance Commission (FFC) and the Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) – possibly through their merger – will also be necessary. We also see merit in a more autonomous Debt Management Office (DMO) to professionalise debt operations, insulate issuance from political pressures and improve transparency.

We feel strongly that adopting such a multi-layered framework and sequencing it alongside other macroeconomic reforms, such as the lowering of the inflation target, would send the strongest possible signal of policy coherence with the aim of a flatter and lower yield curve as a public good in and of itself. It would demonstrate that South Africa is serious about restoring fiscal sustainability, reducing sovereign risk premia, and creating the fiscal space needed to support growth and development, including social wage spending, over the long term.

About Krutham

Krutham (previously Intellidex) is a research-led financial consultancy that works at the intersection of policy, politics and finance. We have dedicated the past 18 years to emerging markets’ sustainable development, leveraging our expertise to drive transformative changes within the financial ecosystem.

We have offices in London, Sandton and Cape Town. From here, we serve clients across the world, including sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and the United States. We leverage the team’s complementary expertise across these locations to maintain a multi-disciplinary approach to the projects we take on. The team includes 35 full-time professionals, including those with PhDs, MBAs, CFA charterholders and chartered accountants with decades of financial services and research experience between them. We also draw on a network of 40 associates.

Our unique offering to the market is being able to combine a deeply experienced capital market and financing capacity with policy and social impact capabilities across public and private sectors. We span the spectrum of capital, serving clients from global hedge funds to philanthropic organisations. At our core, we are committed to helping our clients understand their evolving marketplaces, all while developing financial solutions to social challenges. A firm understanding of the macroeconomy and a detailed appreciation of macro-fiscal policy is a core element of this.

What are we trying to solve?

South Africa’s fiscal position has deteriorated significantly since the global financial crisis. Debt has more than tripled as a share of GDP since 2008, and debt-service costs have risen even faster. Whilst corrective action is being taken today the effects of history are still being felt. Fiscal anchor design must be cognisant of the swings in fiscal position and fiscal credibility over the past 30 years – not simply the near history which has been more positive. This embedded uncertainty is why risk premia exists and partly what affects the shape of the yield curve.

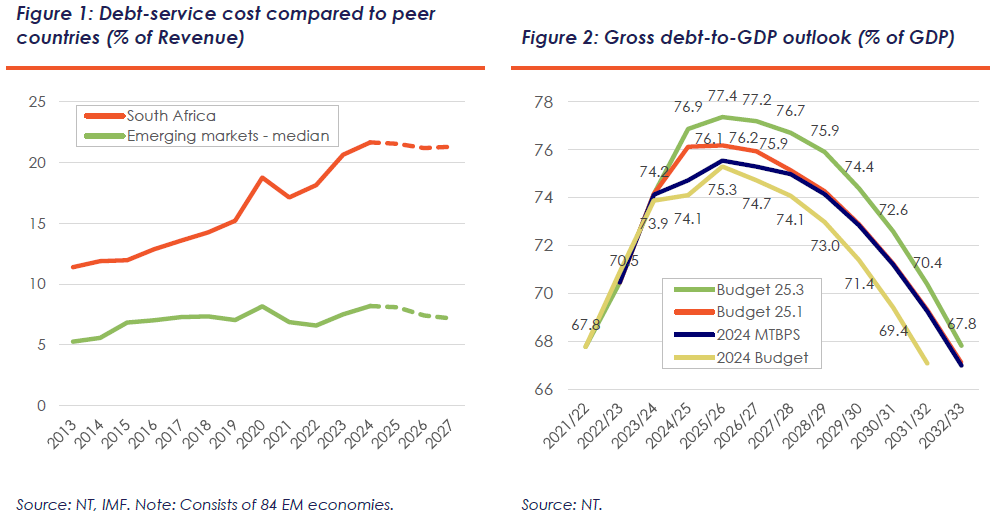

Today, over 20% of government revenue is absorbed by interest payments – far above the median for emerging markets and higher than many stressed peers (Figure 1). In this sense, the core problem is less the absolute stock of debt than the rising cost of financing it. Servicing debt is crowding out growth-enhancing expenditure, weakening confidence and leaving the fiscus vulnerable to shifts in global risk sentiment.

At the core of the problem is fiscal credibility (or more accurately large swings in credibility over history) – whether investors believe National Treasury (NT)’s commitments will be delivered in a given political context and given political risks on the horizon. Increasingly, they are sceptical – rightly or wrongly (NT often protests, somewhat understandably – that they delivering but history of misses in fiscal targets takes a long time to correct). This is visible in the way markets price South Africa’s sovereign risk: 5-year CDS spreads sit well above the emerging market average (Figure 3), while the domestic yield curve is both higher and steeper than most EM peers. Together, these indicators point to a persistent sovereign risk premium, underpinned by scepticism that government can stabilise debt within the current framework.

The erosion of fiscal credibility stems from a few interlinked problems in our view:

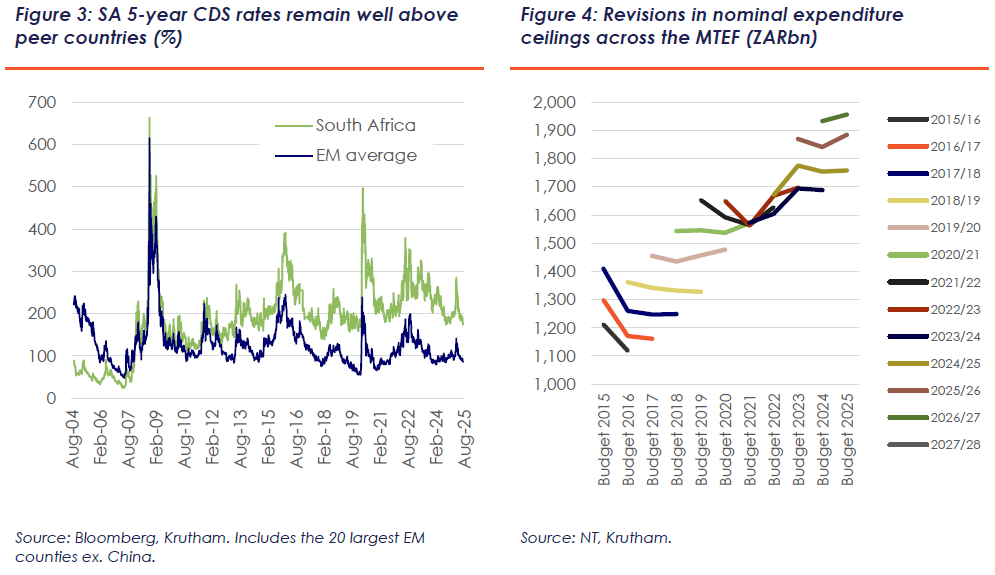

- Repeated slippage on debt stabilisation: Since 2010/11, NT has repeatedly committed to stabilising debt, yet the targets have consistently been revised. The stabilisation year has shifted ten times – from 2015/16 to 2025/26 – while the projected stabilisation level has climbed from 40% of GDP to more than 75%. Each adjustment has underscored a time-inconsistency problem: fiscal policy announcements are not backed by durable shifts in spending or revenue, eroding confidence that commitments will hold.

- Weakening of the expenditure ceiling: The nominal non-interest expenditure ceiling, introduced in 2012, was intended as the main operational rule. In practice, it has been breached and revised numerous times to allow for exemptions – most notably large bailouts to SOEs (see Figure 4). Over time, this has undermined its role as a binding rule. Its objective has never been clearly articulated to the public or markets, and it is not formally recognised by the IMF as a fiscal rule. At the same time, the ceiling does not account for the composition of spending, with no formal requirement for spending on growth-enhancing and investment-promoting spending.

- Systematic forecast optimism: NT’s forecasts have been consistently too optimistic across macro and fiscal variables. GDP growth projections have overshot realised outcomes by an average of 0.5 percentage points in the first year of the MTEF and by 1.6–2.3 in the outer years. Revenue projections have been even more biased. To NT’s credit, South Africa’s economy has underperformed relative to nearly all forecasters, and shocks such as COVID-19 complicated projections. Still, the persistence and scale of forecast errors have had major consequences in a low-growth economy, where small misjudgements in growth and revenue compound rapidly into debt sustainability problems.

- Structural expenditure composition pressures in a weak-growth environment: Even beyond technical rules and forecasts, fiscal commitments have been undermined by rising expenditure pressures against the backdrop of slow growth. The public sector wage bill, increasing demands for social spending and repeated SOE bailouts have steadily consumed fiscal space away from growth-enhancing spending such as infrastructure and the social wage. New policies are often adopted without clear financing, compounding the strain. In this environment, what looks sustainable in one year can quickly unravel in the next. The effect has been to make fiscal planning inherently fragile, eroding confidence that announced targets will be achieved.

South Africa’s credibility gap sits at the centre of its fiscal challenge. Debt and interest costs are climbing not only due to weak growth and spending pressures, but also because markets do not have enough trust in the framework guiding fiscal policy in the current political economy context. In the absence of a credible and consistently applied fiscal anchor, debt-service costs will remain high and sovereign risk premia will remain elevated.

The key proximate issue that arises then is the steepness of the yield curve and the need for a flatter and lower yield curve to be a public good and a sovereign policy objective. Centering this then starts to make clear the need for some kind of anchor as an efficient way to get better fiscal and credibility outcomes.

Addressing this requires more than incremental adjustments. What is needed is a formal fiscal anchor for South Africa, supported by clear design features and institutional safeguards. In the next section, we propose a fiscal anchor framework and the key elements we believe are essential.

Options for a formal fiscal rule

In light of the credibility cycle challenges outlined above, we propose a fiscal rule that combines an integrated numerical framework with strengthened parliamentary procedures. In our view, the combination of both is required to meet the market credibility threshold. The discussion document is not specific enough in these points and leaves the choice far too open ended.

We suggest a unified fiscal rule that distinguishes between an operational (short-term) rule that lays the foundation for sustainability and an overarching objective that becomes binding over time. The design would evolve into three key elements:

- Overarching objective – debt-stabilising primary surpluses. Similar to NT’s current (non-binding) anchor, but formalised. The focus should not be on forcing down debt immediately, but on halting its rise. The best measure of fiscal sustainability is always the debt trajectory – debt that continually rises inevitably signals collapse, while stabilisation and eventual decline are the hallmarks of prudence. Achieving this is difficult, which is why a credible operational rule is essential.

- Operational rule – A compositional share expenditure rule. We propose an expenditure rule expressed as a share of GDP, but importantly, this should be a compositional expenditure rule. A ceiling on total government consumption, with additional binding floors for growth-enhancing expenditure – infrastructure, capital maintenance and selected social spending that supports long-run growth. This dual structure ensures that fiscal consolidation is expenditure-led without crowding out investment. Importantly, this structure will also aid in reducing the sovereign risk perception since confidence in credible growth-enhancing spending can be restored, and in turn lower debt-service costs. Any such rules will need to be cognisant of lower debt service costs over time and the need for additional social wage spending whilst the state seeks also to maximise greater spending on infrastructure also through the private sector (ie off balance sheet).

- Eventual transition – A binding debt level anchor. Once debt has stabilised, the framework should shift to a more binding and lower debt anchor, aligned with international best practice (eg, 60-70%).

From a parliamentary and procedural framework, we propose the following:

- Parliamentary oversight. Each administration should be required to table a comprehensive fiscal plan in parliament within a set timeframe after taking office (a maximum of six months). Unlike the Discussion Document’s generic proposal, the plan must explicitly demonstrate alignment with the fiscal rule – namely, a debt-stabilising primary balance as the overarching objective, and the expenditure/GDP rule with compositional share minima as the operational constraint. Parliament should scrutinise the realism of assumptions (growth, inflation, interest rates – under various scenarios) and the sustainability of borrowing needs. Public hearings and stakeholder consultations would enhance legitimacy, ensuring discipline is maintained without eliminating flexibility. Ultimately however parliament must be given strong and independent views from Chapter 9 style institutions.

- Macro-fiscal strategy. Treasury often assumes markets understand its fiscal strategy, but in practice, markets must reconstruct it, budget by budget, and are still left confused. Whilst Treasury is somewhat more explicit now on its ‘golden threads’ that drive strategy – this is still weakly stated and is relatively new. Over history Treasury has flipflopped and been opaque and secretive to the benefit of nobody. There is a risk that the recent transparency of Treasury could be reversed To remedy this, NT should publish a comprehensive medium-term fiscal strategy, beyond the Budget and MTBPS, clearly articulating the fiscal anchor framework and the strategy to achieve it. This would create a transparent and durable link between stated objectives, operational rules and the broader policy path.

Institutionalisation – the key hurdle

The demand for a more credible fiscal anchor has become clear in market engagement on the Discussion Document, with many different forms proposed and concerns raised. Yet the biggest and most immediate hurdle to adoption, in our view, is the absence of strong independent oversight. Neither the Parliamentary Budget Office nor the Financial and Fiscal Commission currently has the capacity to fulfil this role, and without such oversight, no anchor will be viewed as binding or credible. It is still shocking that they do not undertake detailed independent modelling and forecasting of the level undertaken in the private sector let alone to rival what NT does.

This is also the point at which most concerns about a fiscal anchor converge. Markets worry about creative accounting, overly optimistic forecasts, poorly designed or abused escape clauses and the treatment of SOE bailouts and contingent liabilities that have so often undermined existing rules. They also question whether South Africa can balance flexibility in times of crisis with the binding discipline needed to restore credibility.

Addressing these concerns will require building independent fiscal councils with the mandate and resources to scrutinise fiscal plans, evaluate assumptions and monitor compliance transparently. This will take significant investment in capacity, but it is the most important piece of the puzzle. Strong and credible oversight, combined with a rules-based anchor, is the channel through which market confidence can be rebuilt. In our view, this should be National Treasury’s first and most urgent priority and it remains the single biggest obstacle preventing the introduction of a credible fiscal anchor. Such councils could be formed from merging the PBO and FFC though serious and weighty leadership would be required to establish credibility.

There is also an additional need for an independent Debt Management Office (DMO). While Treasury’s Asset and Liability Management division currently performs this role, a more autonomous DMO could strengthen market confidence by professionalising debt operations, insulating issuance decisions from political pressures and providing greater transparency on borrowing strategies, maturity profiles and contingent liabilities. Together with an empowered fiscal council, such an institution would anchor credibility not just in rules, but also in the institutions tasked with implementing them.

NT and SARB coordination

Sequencing of macroeconomic reforms matters. A more binding and credible fiscal anchor should be introduced in parallel with, or as close as possible to, the formal lowering of the inflation target. Anchoring fiscal policy at the same time would help reduce the sovereign risk premium, compress long-term rates, and give both fiscal and monetary authorities greater room to manoeuvre. We therefore urge NT to prioritise the adoption of a formal fiscal anchor so that it is aligned with the inflation target shift – which the SARB has already adopted de facto.

We recognise that this sequencing carries more difficult short-term fiscal optics, including weaker nominal GDP growth and slower revenue performance in the early years. Yet the long-term payoff would be substantial. Lower debt-service costs would improve fiscal sustainability and create additional fiscal space over time. Put differently, the two reforms are mutually reinforcing: a credible fiscal anchor would increase the chances of the 3% inflation target being embedded in expectations, while the lower target would, in turn, reinforce the credibility and effectiveness of the anchor by reducing borrowing costs and easing fiscal pressure.

Coordination should be premised around key goals not just simplistic ‘macroeconomic stability’ which seems too basic. Instead the sovereign level commitment to a lower and flatter yield curve as a public good should be central to coordination with the Macro Standing Committee providing more regular updates on its work to achieve this aim. Currently there seems to be a breakdown in the relationships between the institutions and through this committee given the actions of all sides around the current inflation target debacle. This situation should be an opportunity for future strengthening.

Conclusion

South Africa’s fiscal credibility challenge lies not in historic volatility and cycles in credibility and the absence of stated intentions but in the repeated slippage, weak enforcement and lack of institutional support behind them. A formal fiscal anchor offers an opportunity to break this cycle – but only if it is designed with both numerical clarity and institutional strength.

We believe the framework we propose – a debt-stabilising primary balance as the overarching objective, a compositional expenditure rule to protect growth-enhancing spending and a later transition to a binding debt anchor – provides a balanced, achievable path. Embedding this in parliamentary processes, underpinned by an explicit macro-fiscal strategy, would ensure transparency and accountability.

Most critically, success will depend on institutionalisation. Capacitated fiscal councils (perhaps born out of the FFC and PBO – with appropriate budget and weighty leadership) and an independent DMO are essential to give the anchor credibility in the eyes of markets and to ensure that commitments are translated into durable outcomes.

Adopting such a framework and sequencing it alongside other macroeconomic reforms, such as the lowering of the inflation target, would send the strongest possible signal of policy coherence. It would demonstrate that South Africa is serious about restoring fiscal sustainability, reducing sovereign risk premia, and creating the fiscal space needed to support growth and development over the long term. All this would lead to a lower flatter yield curve as they key proximate goal.