By Peter Attard Montalto

The president’s response to the coronavirus has been solid while the Reserve Bank upgraded its response to bazooka-level; but the economy still faces severe contraction, says Peter Attard Montalto, Intellidex’s head of capital markets research.

The 21-day lockdown to slow the spread of the coronavirus will have a severe economic impact – and there is a strong risk that the lockdown will have to be extended. President Cyril Ramaphosa announced the lockdown and some economic support measures in a well-received, robust and very clear speech on Monday night, which clearly saw him stepping up to the plate on a range of issues, related both to health and the economy.

It was a dramatic move but a strong response, because SA is acting before the first local death from Covid-19 and at a much earlier case load than other countries taking similar measures. This shows resolve certainly, but we should also be cognisant of the much higher underlying risk in South Africa related to health issues, poverty and seasonality.

While a lockdown is enforceable in middle class and affluent areas, the key will be in townships and the informal economy. These large and densely populated areas see poor living conditions that will be hard to patrol and where basic services (such as shops for essentials) can be some distance away. We therefore are sceptical of the effectiveness of such a move in these crucial areas. That is not to say there was any other option – we don’t think there was – either in terms of the epidemiology or the politics; the point is that we should not expect this to stop spreading, merely to slow it down.

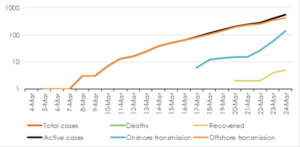

Testing will be ramped up during the lockdown to identify and isolate pockets of outbreak more effectively. However, of the 12,800 tests carried out so far, we believe 80% or so have been in the private sector. The public sector, while increasing its rate, is still not near to hitting the required rate of 5,000 tests a day. As this starts to happen, however, we should get a better idea of intra-township spread, which is crucial given that is also where the highest prevalence of underlying respiratory illness is. This will initially cause a marked steepening of the case curve.

Economic impact

The economic impact will be severe, clearly, with all businesses except essential services being forced to close. This includes mines and all industry except those involved in refining, food and medical supplies manufacturing. Banks will still be able run but only with core-function staff.

However, the ability for traders locally to still operate and the JSE to remain open is an important point to recognise.

The severe suppression of economic activity for three weeks would represent a drop of 5.8% from full-year GDP. Consumption of essentials will remain while some output will happen for the manufacturing of essentials. Trade will largely stop but agriculture will not. However, many parts of GDP will be displaced and not lost (for instance with mines, where we have often seen decent recovery curves after loadshedding over a period of three to six months).

Economic stimulus package

Ramaphosa announced a set of economic interventions and the Reserve Bank is contributing with the emergency measure of buying an unspecified amount of government bonds, with varying maturities, to ease the liquidity crunch. It is the first time the Reserve Bank has intervened in the bond market in such a manner.

In a statement the bank also said it would offer repurchase agreements, or repos, for periods of seven days to longer-term maturities of up to 12 months.

After deteriorating liquidity conditions and the bond market becoming effectively dysfunctional this week, the SARB has decisively stepped up to the plate and upgraded its tool kit to a bazooka.

After the repo rate cut last week and then the Reserve Bank’s liquidity measures announced on Friday (which were incentives and optionality-based for banks only), more was clearly needed. Liquidity needed to be forced into the system and the bond-buying programme offers that. It pumps cash directly into the secondary market and adds a backstop bid to the market where there hasn’t been any in recent days.

This is a programme announcement, it gives the SARB the option. We think it will indeed be doing this in the coming days and weeks, but the expansion of the tool kit is the announcement, not a firm commitment it is doing it. This difference is important. The SARB wants to keep this open-ended, unlimited and mysterious. The “fear” factor works to its advantage (the bonds immediately reacted positively) and it reduces the amounts that need buying as a result.

Looking at the economic measures announced by Ramaphosa, it is very hard to describe this as a stimulus. The broad takeaway is, as expected, there is no macro-fiscal stimulus into the economy given the lack of funding space. We also don’t really see this providing meaningful support to prevent a deep fall in GDP in Q2, but more that it creates a lessening of the existential question for SMMEs in particular and an up-ramp for recovery by keeping businesses alive and people employed.

There is actually very limited call on fiscal resources at all at this stage. We look at this below.

The measures were:

- A private sector-led Solidarity Fund which is being seeded with R150m of fiscal money (we believe this comes from the contingency reserve) plus R2bn from the Rupert and Oppenheimer families. Estimating the total size of this at the end-point is hard but we could see it reaching 10bn in total if the South African diaspora contribute in a meaningful way. In macro terms this is small.

- An informal sector support net, though no details were forthcoming.

- Early payment of some social grants.

- The existing Temporary Employee Relief Scheme will be utilised to extend relief to companies and prevent layoffs (this was already announced on 17 March with no clear additional resources yet).

- Sick pay will be paid through the Employee Compensation Fund (existing, so no clear additional resources yet).

- Commercial banks are exempted from the Competition Act to enable a unified approach to forbearance – we still believe this is the main route to support into the economy in significant multibillion-rands.

- Work to unlock the UIF funds for payment is ongoing. This would not be a new fiscal resource but would involve tapping the 150bn net asset surplus the fund has with easier rules.

- The Employment Tax Incentive will be extended to provide 4-million workers with a subsidy of up to R500 a month, where they earn less than R6,500/month, for a maximum of four months. This is a fiscal cost of R8bn, which will have to come from internal rotation under the existing expenditure ceiling.

- SARS will accelerate reimbursements and tax credits, changing from twice yearly payments to monthly (this is fiscally neutral but will help liquidity of firms).

- Firms with less than R50m turnover will be allowed to defer 20% of PAYE liabilities for four months and an unknown portion of corporate income tax payments for six months. This is expected to target 75,000 SMMEs. This is broadly a transfer of liquidity from this fiscal year to next. We will watch this closely: tax holidays are likely to be an area to be bolstered into tax write-offs as things worsen, we believe.

- Government is exploring the reduction of UIF and Skills Development Fund payments by firms. This is likely to be in the order of a few million rand – hard to say at this stage, but it would not affect the core fiscus.

- A R500m SMME fund by the small business development department, which had already been announced.

- A R3bn IDC fund for industry support (expected to be for larger businesses and is not on the balance sheet for the fiscus).

- Tourism department will add R200m to its existing support fund (expected to be within existing budgets).

Overall then, we can find only about R8.125bn in new spending, with possibly a few billion rand more for employment relief yet that is yet to be defined, some deferments through tax holidays and about 13.7bn of other funding. These numbers do not move the dial at the macro level.

Like in other countries, we expect authorities to come back with more iterations week by week as the impact is felt and the political pressure builds. We should therefore expect more to come, just as we expect an off-cycle April meeting of the Reserve Bank’s monetary policy committee.

For more i-Blog insights, click here