To an equity analyst, ratings agencies are an odd thing. An issuer of debt securities pays a company for its analysts to produce an opinion on how likely the issuer is to pay its debts. It is the equivalent of “issuer paid” research in the equities world, when a company pays an analyst to produce an opinion, one which is invariably “buy”. Such research has little influence on investment decision-makers.

Of course, just as in the equities world, the fund managers making the buy and sell decisions on bonds and other debt securities cast a wary eye at official ratings as of only passing interest. Which is why SA bond yields have been rallying long before S&P Global announced last Friday that it had upgraded SA’s credit rating one notch and was maintaining a positive outlook.

Indeed, the performance of the bond market has been remarkable, with yields reaching decade lows. The rally results from positive momentum on many fronts, particularly the medium-term budget policy statement, which confirmed that SA was on track for a primary surplus, and the shift of the official inflation target to 3%, which implies lower future interest rates.

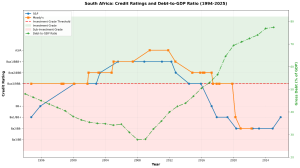

However, while fund managers see credit ratings as merely advisory, they do have a material impact on index inclusion. The biggest international bond indices only include “investment grade” debt, and funds that track those indices will only buy debt that is included. SA remains in subinvestment grade territory, two notches below on S&P’s scale. S&P had downgraded SA to junk territory in 2017, with Moody’s holding out until the beginning of Covid-19 before it too tipped SA into junk.

Getting back to investment grade is clearly the goal, with a substantial prize at the end of it. Not only would re-admittance to global indices lead to a substantial jump in global flows to SA debt, but it would signal that SA was investible overall. This has many consequences, including that SA financial institutions would be seen again as worthy counterparts, able to be trusted to hold assets in custody, for example. There are many services that global counterparts will only buy from institutions operating in investment-grade countries. Lower risk spreads on government debt reduce rates that every debt issuer across the economy pays, including our banks, so the cost of capital falls.

How long will it take SA to get there? The interesting parallel to our current circumstance is the early 1990s. In the dying days of apartheid, government finances were bust. National budgets were running deficits of 8% of GDP, with the economy in a tailspin. Thanks largely to being unlendable on international markets, debt was relatively modest at less than 50% of GDP.

However, one of the achievements of the Mandela government was to rapidly stabilise the financial picture. And that led to the last time S&P upgraded SA to BB, when it introduced its rating in 1994. It took another six years, to 2000, for the rating to progress up the two notches to investment grade, all while the budget balance improved, culminating in two years of budget surpluses just before the global financial crisis when S&P had SA at two notches above junk.

The postcrisis recession and the arrival of Jacob Zuma’s presidency marked the beginning of decline, with budget deficits back to almost 5% of GDP every year, ballooning the debt stock to the record 78% of GDP it will reach this year (from 26% in 2008).

To maintain the trajectory to return to investment grade, SA will have to remain highly disciplined on fiscal management. While this year it will spend less than it earns in revenue on basic expenditure, debt service costs remain a huge burden. So, the “primary” deficit is now half a percentage point positive but the main budget balance is still minus 4.5% of GDP. SA thus now earns slightly more than it spends before interest payments, but debt service costs still push the overall budget into deficit.

The five percentage points of GDP difference represents the amounts the government is paying in interest on its debt. The primary balance allows it to tackle the debt pile, gradually whittling it down by reducing issuance. Sharply improved bond yields mean the debt it issues now will cost it less, helping to reduce debt service costs. The medium-term budget showed that finances have improved significantly over the six months since the previous budget was eventually tabled, and it now expects the trajectory of debt to GDP to accelerate downward. Even so, its outer forecast for 2032 has debt at 68% of GDP.

In 2000, when S&P upgraded SA to investment grade, the debt burden was just less than 40% of GDP. SA is perhaps decades away from that level. But investment grade reflects the government’s ability to service debt, which is easier when the economy is growing and interest rates are low. Mauritius, for example, is running a debt-to-GDP of more than 80%, but holds investment grade.

The central question isn’t whether the Ramaphosa administration can maintain discipline — the record shows it can. The question is what comes after.

Visibility beyond the current presidency remains cloudy, and the agencies will demand clarity on that succession before restoring investment grade. They’ve been burnt by SA before, upgrading based on promise only to watch profligacy return. This time they’ll wait for proof that fiscal discipline transcends any individual leader.

The prize of investment grade is substantial, with lower borrowing costs and billions in index driven inflows. But it will require something SA hasn’t demonstrated in decades: that sound economic management survives political transitions. Until the agencies see that, investment grade will remain in waiting.

- Dr Stuart Theobald is chair of research-led consultancy Krutham. This article first appeared in Business Day.